When the EU launched its Sustainable Finance Action Plan, it wanted to increase the flow of funds towards ‘green’ economic activity, aligning with the EU’s Green Deal and the 2015 Paris Agreement. This includes Article 2.1C which aims to align public and private financial flows with a temperature rise limit of 1.5°C.

What Is Sustainable Finance and Why Is It Important?

The EU defines sustainable finance as ‘the process of taking environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into account when making investment decisions in the financial sector’.

Since 2015, we have seen a multitude of legislative proposals to increase sustainable finance flows, directing investment towards ‘green’ activities in the EU and beyond. Understanding this myriad of acronyms – and how they connect – can be challenging, especially for investors operating globally. Here, we attempt to define and explain some of the key terms, how they are related, and why they are relevant for sustainable finance, the global financial market and food systems.

Corporate disclosure serves many important roles, not least to investors when reviewing ESG and other factors. It is essential for much of FAIRR’s work, including the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index, a flagship product released annually assigning ESG scores to the largest listed animal agriculture companies based on corporate disclosures. Access to the Index helps investors make informed decisions that help minimise material risks and maximise opportunities for long-term growth.

Corporate Sustainability Disclosure

The CSRD (formerly NFRD), EFRAG, ESRS, and the CSDDD

Regulations – such as those covered here – elevate required company disclosures and facilitate the integration of sustainability into the investment decision making while aiding investor protection against greenwashing.

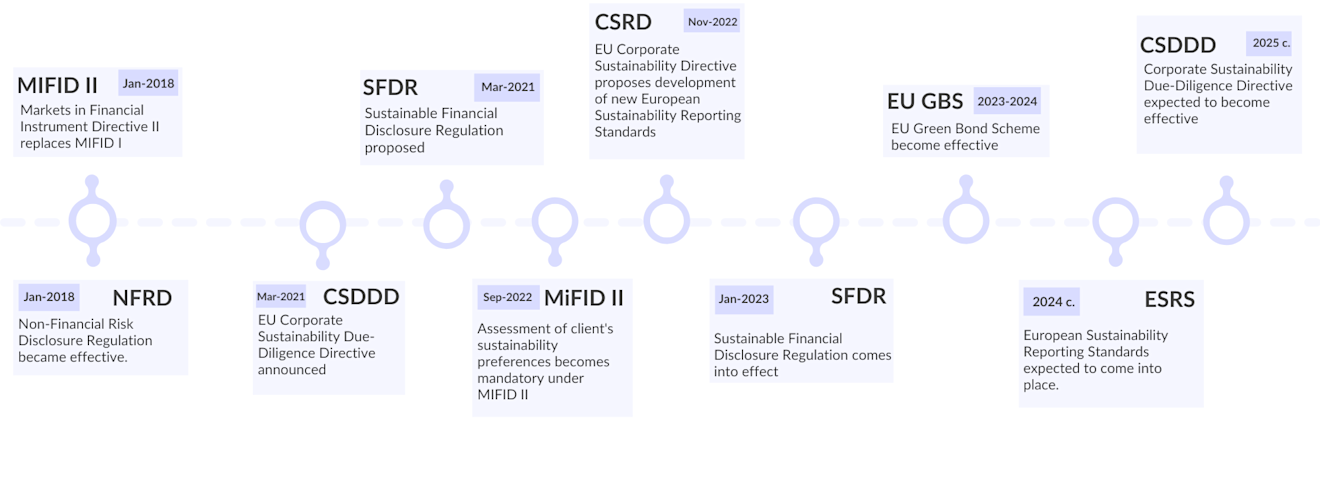

In 2014, the EU adopted the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which required listed companies (with over 500 employees) to report both on how sustainability issues affect them, as well as on their own impact on people and environment – a concept known as ‘double materiality’. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) acts as an update to the NFRD. It complements other regulations by harmonizing and broadening the scope of disclosure, requiring all listed companies in the EU (including listed SMEs, but not micro-enterprises), as well as other large companies, and certain non-EU companies, to report against specific sustainability standards. Those standards, referred to as the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), are currently being developed by an independent body – the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG).

In November 2022, the CSRD proposal was approved by the European Council. Proposals for sector-agnostic ESRS (which all companies that fall under CSRD will have to report on), were submitted to the Commission at the same time. After these are approved, they will be used by companies that fall under the CSRD scope. The CSRD is expected to enter into force in 2024, with the first submissions due in 2025. The EFRAG is currently still developing sector-specific standards, including for the Food and Beverage and Agriculture and Farming Sectors, which will complement the sector-agnostic ESRS by requiring reporting on additional topics in areas unique to each sector. Proposals for these standards are on track to be published in time for the new ESRS to be implemented in 2024.

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) is another EU Commission proposal from early 2022 that aims to make companies responsible for human rights violations and environmental standards along their value chains. This will complement the current CSRD by adding a duty for companies to perform due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for external harm resulting from adverse human rights and environmental impacts in the company’s own operations, its subsidiaries and in the value chain. The European Council accepted a set of CSDDD proposals in early December 2022, but these have since been questioned for not including financial institutions in their scope.

At a global level, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), established at COP26 to develop a comprehensive global baseline of sustainability disclosures for the capital markets, published a new proposed set of ESG standards in March 2022, due to be finalised and issued in 2023. In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) also proposed detailed mandatory disclosure from public companies and registered investment advisers and funds. The proposals were due to be finalised by October 2022, but this self-imposed deadline has been missed. Both the ISSB and SEC proposals include the requirement to disclose Scope 3 emissions, an emissions category especially relevant for assessing carbon footprint in the agriculture sector. Given that over 90% of emissions in the livestock industry can fall under Scope 3, this requirement would help investors in the sector assess their ‘financed emissions’ and improve their own ability to report, for example against the SFDR.

Financial Market Regulation

The EU Taxonomy Regulation

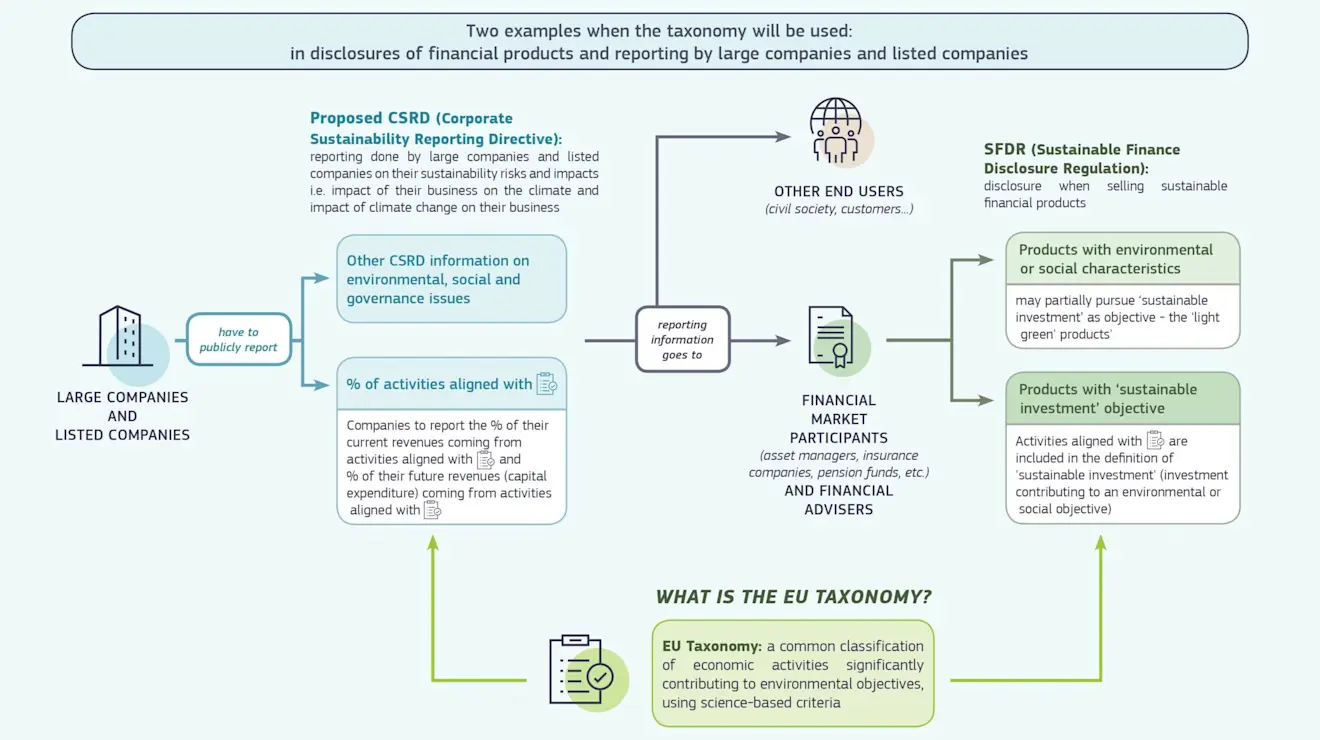

The EU Taxonomy acts as a classification system of economic activities that make a ‘significant contribution’ to at least one of six environmental objectives, while doing ‘no significant harm’ to any of the others, and adhering to minimum social safeguards. The environmental objectives are climate change mitigation and adaptation, water resources, circular economy, pollution and biodiversity. The aim is to clarify what is sustainable and what is not, and encourage companies to shift towards greener practices while countering greenwashing.

Several elements of the EU Taxonomy have been criticised. In late 2021, a group of investors representing $3.5 trillion convened by FAIRR called for the EU Taxonomy to be more robust and science-based, and expressed concerns over some proposals for agriculture sector criteria to align with eco-schemes under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). A new Climate Delegated Act for Agriculture is yet to be published (at the time of writing). The Taxonomy regulation has also been questioned for being a ‘binary’ rather than a ‘traffic light’ system, potentially opening it up to influence by corporate groups with vested interest, and indeed the inclusion of nuclear in the Taxonomy has led to increased interest from investors.

How does the EU Taxonomy fit within the Sustainable Finance Framework?

Source: European Commission

SFDR – Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation

Since March 2021, the EU has required financial market participants and advisors based in the bloc to disclose how their investments contribute to sustainability objectives. On January 1st 2023, the SFDR ‘level 2’ rules came into force. Investors are expected to allocate funds into one of three categories – Article 6, Article 8 and Article 9. More information on the SFDR can be found in FAIRR’S previous blog on the subject. To be eligible for Article 9, the ‘greenest’ type of investment, the fund must have at its core a sustainable investment objective that aligns with the EU Taxonomy criteria. Investors require granular information disclosure from companies, as well as clarity on what classifies as a green economic activities in the Taxonomy framework, to accurately report against the SFDR.

In recent months, many big investors have reclassified and downgraded their funds from Article 9 to Article 8. This move is a response to increased pressure from national regulators, and an amendment to MiFID II in August 2022 where sustainability suitability criteria highlight Taxonomy-aligned products as a potential option for meeting clients’ sustainability preferences (see below). This has nudged asset managers to launch/relabel funds to attract flows, or face trouble marketing non-ESG funds. While investors are less likely to face greenwashing claims as funds are downgraded, it also means that less information disclosure is required from them, and therefore may not contribute to the EU’s overall green finance objectives.

Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (MiFID II)

MiFID II replaced MiFiD in 2018 and aims to regulate financial markets in the bloc and improve protection for investors. In September 2022, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) finalised guidelines on ESG-related changes to the directive, intended to include sustainability considerations that will help increase ‘green’ financial flows and avoid greenwashing. The changes consist of a new requirement to assess clients’ sustainability preferences, with three options for clients: alignment with the Taxonomy; a percentage in ‘sustainable investments’ as defined by the SFDR; or a quantitative or qualitative assessment of Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs).

Green Bonds Standard: EU GBS

The European Green Bond Standard (EU GBS) is another component of the EU Sustainable Finance Action Plan – a voluntary standard to help scale – and raise environmental ambitions of – the green bond market in the EU. A proposal for this regulation was published in July 2021, and requires that bonds with a “European Green Bond” label must exclusively fund environmentally sustainable economic activities that align with the Taxonomy. There has been disagreement amongst the Commission, Council and Parliament on several elements. The final version of the EU GBS is expected to be published by the end of 2022, after which the legislative proposal would apply from 2023 or 2024.

Navigating the Regulatory Landscape

Since the launch of the EU Sustainable Finance Action Plan, a range of acronyms have entered the regulatory landscape, and it is possible more will follow, making it confusing to navigate. It is hoped that the article has clarified some of the existing terms being used by the EU and the interdependencies between various regulations. While navigating this landscape may prove difficult at times, those complying with the requirements should rest assured that it comes from a place of good intentions, and that ongoing efforts to improve taxonomy usability and to align it with other sustainable finance regulation should provide further clarity in time.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.

Written by

Policy Director