Executive summary

Demand for animal products in recent decades have intensified a number of sustainability issues. High levels of consumption are fuelled by low, often subsidised, prices that do not correlate with their true production costs.

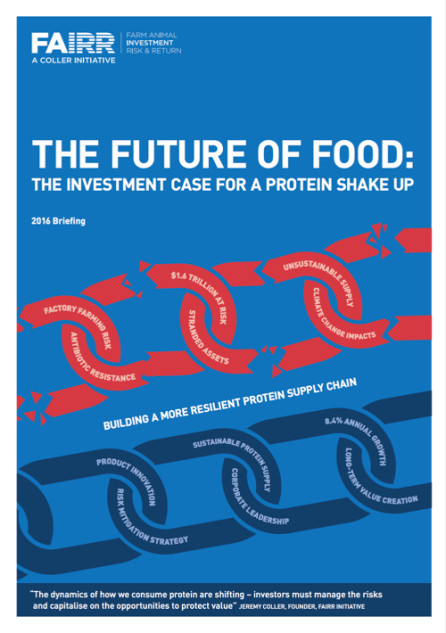

Here we examine the investment risks linked to the over-reliance on intensively farmed animal products, offering strategies to mitigate this risk. Alongside this, the briefing reviews the investment opportunities presented by a transition towards more diverse sources of protein to capitalise on current market trends.

The livestock sector currently accounts for 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs); more than the global transport sector. Research by Chatham House has indicated that it will not be possible to limit temperature rises to below 2°C – the goal agreed at UN climate talks in 2015 – if livestock production and consumption are not reduced.

"It is critical for consumer-centric food and beverages companies…to focus on changing consumer preferences and adapt accordingly. This strategy will be essential to drive long term growth"

While there are efficiency gains to be made in production (for example, mixed crop-livestock systems to make best use of available land) and the potential of technological innovations that could reduce some detrimental impacts of livestock production (for example, adjustments to animal feed, and methane capture), they are limited and only part of the solution.

Crucially, current levels of production are unsustainable, with negative environmental and social consequences leading to financial risk, as FAIRR’s 2015 risk report outlines. Combined, these impacts could prove costly, with a recent University of Oxford study suggesting that if unaddressed, the public health and environmental expenses associated with the increased demand for animal products could be up to $1.6 trillion globally by 2050.

"A recent University of Oxford study suggests that if unaddressed, the public health and environmental expenses associated with the increased demand for animal products could be up to $1.6 trillion globally by 2050."

The possible accumulation of these factors and their collective impact weakens supply chains and makes them more susceptible to disruption. The future sourcing of protein will play a significant role in responding to these problems and ensuring supply chain security.

In addition to helping mitigate the risks, there are also upside opportunities to be seized by investors and companies who show leadership on this issue. Market analysis and sales over recent years have shown that consumers are increasingly aware of the detrimental impacts of a heavily meat-based diet and are moving to cut back on its consumption. With the clock ticking on climate change and an imminent public health crisis, some governments are already moving to legislate against highly polluting and potentially carcinogenic foods. Forward-looking investors and large food companies can move now to respond to and help shape this burgeoning market, and in the process help to build supply chains that are more resilient to future shocks.

Environmental and social risk

Over the past half century, the growth of the factory farming model and the increasing overconsumption of animal products has been taking its toll on the environment and human health. Consumers in early industrial countries now eat far more protein than is needed for optimum health or that the world can sustainably supply. According to current trajectories, by midcentury global meat production is projected to double from its 1999 levels, which will be catastrophic for our climate. Research by Chatham House has indicated that it will not be possible to limit temperature rises to 2˚C the goal agreed at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP21, in 2015 – if livestock production and consumption are not reduced.

GHG emissions: Livestock production accounts for 14.5% of GHG emissions (more than the global transport sector); with research providing strong evidence that it will not be possible to limit temperature rises to 2˚C if meat and dairy consumption is not reduced from current levels.

Resource use: Animal agriculture contributes to resource scarcity that can cause local opposition and conflict. As an example of water inefficiency, it can take 1,800 to 2,500 gallons of water to produce just 1 pound of beef. This can result in water stress in water-scarce regions.

Deforestation and other environmental impacts: Environmental impacts are wide-ranging and include deforestation, soil degradation, water and air pollution (all with potentially material impacts for investors).

Animal welfare: Increasing demand for animal products is driving industrial livestock production, dependent on practices such as close confinement and genetic manipulations focused on high production at the expense of welfare. This model comes with significant reputational risks, especially with consumers increasingly paying attention to welfare and valuing brand transparency.

Public health: Overconsumption of animal products is linked to health issues such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer.11 Overuse of antibiotics in intensive livestock production contributes to antimicrobial resistance. The growth of the livestock sector has also led to food safety scares and pandemics, such as avian flu.

Supply chain disruption: The collective impact and possible accumulation of these factors mean that supply chains reliant on exploitative and unsustainable practices are inherently more susceptible to disruption. This has been seen with overexploited fisheries, and egg supply chains impacted by avian flu.

The costs of the current food system are borne by businesses as well as individuals. Taking just one example, poor eating habits are reported to cost employers around £17 billion a year, or 97 million lost working days in the UK alone. There has been an increasing adoption of ‘western’ diets that are high in processed foods along with fat, sugar and salt. This is, in turn, contributing to the global spread of ‘diseases of affluence’ crises, such as heart disease, hypertension, obesity, and increasing rates of cancer. At the same time, our global food system is a major driver of climate change, being responsible for more than a quarter of all GHG emissions, and linked to a number of other crucial sustainability issues.

It will not be possible to limit temperature rises to 2˚C – the goal agreed at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP21, in 2015 if livestock production and consumption are not reduced.

The call for protein diversity and an emphasis on promoting the availability and affordability of plant-based proteins is not a request for abstention from animal products, but rather the development of sustainable supply chains that do not rely on a single protein source.

While some progress has been made through improvement in livestock production practices (for example, certification schemes such as the RSPCA Assured in the UK, the Global Animal Partnership scheme in the US, the Marine Stewardship Council, or zero-deforestation commitments), there remains a need for a greater focus on the role of plant-based protein sources as an important part of a resilient supply chain.

"The growing ranks of novel protein sources and potential replacements appeal to the everyday consumer, foreshadowing a profoundly changed marketplace in which what was formerly ‘alternative’ could take over the mainstream"

Acting on this now is in the long-term interest of investors and retailers alike, who can seek competitive advantage by developing strategies to address this issue. Proactive companies can help to future-proof their infrastructure and investments as, without such affirmative action, the collective impact and possible accumulation of these risk factors weaken supply chains, and makes them more susceptible to disruption.

"Consumers are much more aware of the health impact of food than they were 10–15 years ago. They are also ready to pay premium for quality food."

Martijn Oosterwoud, Head of Client Portfolio Management, RobecoSAM

What does this mean in practice?

The call for sustainable protein supply chains is not a demand for ruling out animal products entirely, though some companies and consumers will identify that as the commitment they want to make. From a health and sustainability perspective, a varied diet18 that includes some animal products should mean:

Diversifying the range of protein on offer and prioritising choices that have less impact on health, land, water and the climate: for example, opting for sustainably sourced fish or poultry instead of beef, or beans instead of pork.

Moving away from meat and dairy as the dominant ingredient in every menu option to instead making them an occasional compliment to a meal.

Selecting lean cuts for meals that do feature meat, and reducing or eliminating the use of red and processed meat (such as bacon, ham and sausages).

Sourcing food that meets a credible certified standard like Animal Welfare Approved or the Global Animal Partnership for high-welfare methods of farming in the US, the Marine Stewardship Council certification for sustainable fish and the Soil Association for organic certification in the UK.

Producing and procuring appealing and accessible alternatives to meat-based on plant proteins and new food tech innovations.

Driving factors behind the market shift

Market analysts acknowledge that increasingly consumers are making the link between food and health, and researchers estimate that demand for meat substitutes – products prepared from tofu, tempeh, textured vegetable protein, seitan, Quorn and other plant-based sources – will grow by 8.4% annually over the next five years. Other studies predict that alternative proteins could constitute a third of the total protein market by midcentury. Already, nearly half of Americans are reported to consume non-dairy milk, with this trend attributed to concerns over heart health and weight loss.

In terms of the driving factors behind this trend, the public health evidence base for such a shift is increasing: for example, within recent months there has been widespread reporting of research that animal protein is a significant factor in the obesity crisis and that red meat is linked to kidney damage. The World Health Organization also recently classified red and processed meats as carcinogenic.

However, despite significant red flags from the medical profession and scientists as seen previously with regard to the tobacco industry, most governments have, so far at least, run shy of tackling this issue head-on. How long governments can continue to prioritise trade over public health and the environment is a matter of debate.

"Environmental impact food labels can help consumers compare across and within food product types and make more sustainable and environmentally-conscious decisions. "

What are some of the alternatives to animal protein?

Dairy-free milk: Almond, flax, hemp, rice and soy, which are often fortified with additional calcium and nutrients.

Grains, legumes, nuts, pulses and seeds: Beans, lentils, oats, peas, and quinoa are just a few foods in this category that are full of soluble fibre, protein, and essential nutrients while also being low in saturated fat.

Insects: Opinions differ on how readily these will be welcomed into the global food chain, although they are already consumed in some countries. Aside from human consumption, these could provide a valuable alternative source of animal feed and free up plant-based foods for human use.

Lab, cultured or ‘clean’ meat: However, this technology is estimated to be several years away from being feasible at scale.

Macro and micro-algae: Macro-algae are seaweeds, like dulse and kelp. Micro-algae is generally used as a wholefood ingredient and includes species such as spirulina and chlorella.

Meat substitutes: Many of these are still based on soy (e.g. tempeh or tofu) or wheat-protein (e.g. seitan), but there are also a broader range of alternatives such as pea, grain and nut-based products.

"People don’t want to rely on animal-derived materials and there is a lot of pressure on companies to switch to plant-based alternatives. It’s not just a handful of vegans asking for this."

How investors should respond

Staying ahead of policy and regulatory frameworks

Companies need to embed sustainability into all areas of their business. While making the case for addressing readily quantifiable environmental impacts may be an easier short-term win – there are, for example, clear up-front cost savings to be made in reducing energy consumption and tackling food waste – taking a medium to long-term view of sustainability risks and opportunities also requires a focus both on how protein is sourced and at what cost.

An example can be seen in the livestock sector, which currently accounts for 14.5% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions: more than the global transport sector. While there are certainly improvements to be made in production and distribution efficiencies, research indicates that these have only a small part to play; with, for instance, a reduction in food waste likely to lower food-related emissions by just 1 to 3%. In contrast, adopting global dietary guidelines with lower meat consumption would cut food-related emissions by 29%, vegetarian diets by 63%, and vegan diets by 70%.

As the effects of climate change become more immediately apparent, governments may increasingly legislate and insert regulations that dictate the need for progressive action on the part of businesses to address a wider range of sustainability concerns. For example, Denmark is considering proposals to introduce a tax on red meat, with the Danish Ethics Council citing the livestock industry’s immense impact on climate change. Chia is another notable exception that is reticent to declare against a meat-centric diet, which – on the basis of domestic obesity and diabetes problems – has refocused efforts on urging its citizens to eat 50% less meat than at present. Moving beyond policy pronouncements to tangible taxation and quota frameworks would have a major impact on companies that have not moved to diversify their offering.

For a response to climate-damaging food to be effective, while also contributing to raise awareness of the challenge of climate change, it must be shared. This requires society to send a clear signal through regulation.

Mickey Gjerris, Chairman of the Council’s working group, Danish Ethics Council

Building resilient supply chains

Market changes and climate shocks are both critical areas of risk for supply chains, and factory farming has broad exposures to both. Exposure through the media of animal cruelty can seriously affect a company’s reputation and lead to a drop-off in sales, but the demands of manufacturers are such that current exploitation can seem hardwired into the system. Meanwhile, the rapacious demands of the meat production sector play a major role in using up the world’s land and resources. While it takes 2,000 litres of water to produce a kilo of soybeans, 43,000 litres are required to produce the same quantity of beef. Meat is the most damaging product to the environment, with beef having the largest carbon, nitrogen, and water footprints per kilogram of product. Beef and dairy create the most intensive impact on our environment with, per unit of protein, beef production causing GHG emissions estimated to be up to 150 times those of plant proteins such as legumes. The least impactful animal product in terms of GHG emissions, chicken, still causes an estimated 40 times higher impact than legumes. None of these resource demands are sustainable in a scenario of increasing population, alongside rising temperatures and sea levels.

"The supply chain has become more important than ever to the commercial foodservice industry."

Through working in collaboration with others, companies can implement urgently needed collective actions across and along the supply chain to address broader food system challenges. Around two-thirds of consumers feel that independently verified sustainability standards increase their confidence in a brand, and initiatives such as the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef can help to mitigate some of the most serious risk factors, but so far these initiatives have not gone far enough, and too few firms are taking these measures seriously. To help with the evolution to a less meat and more plant-based diet, partnerships and long-term investments in food producers can help to build skills, knowledge and capacity, helping to ensure that supply chains are future-proof. There is a range of ways that companies can implement innovation in-house on this issue. Such initiatives do not necessarily need to come with an expensive research and development price tag, but can often take the form of low-cost measures: inspiring a modified dietary approach through appealing on-packet recipe suggestions that do not default to meat, factoring sustainable protein in as a category when making decisions on purchasing and placement, and thinking creatively about how to encourage consumers towards less-meat and plant-based options. Those companies that take a far-sighted approach to scoping and shaping this burgeoning market will position themselves for an ample market share, while others who lag behind may well find their current positions ebb away as consumers change allegiance and a warming climate makes existing food production models obsolete.

"The idea of making [plantbased] products is attracting entrepreneurs and venturecapital firms who think that the traditional food industry is ripe for disruption because it is inefficient, inhumane and in need of an overhaul."

Tapping into a growing consumer base

In recent years per capita consumption of meat, particularly in developed countries, has levelled off or even declined. Much of this shift can be attributed to people who are cutting back on rather than cutting out meat entirely. However, in Britain alone, the number of vegans has risen by more than 360 per cent over the past decade, with close to half of those 542,000 found in the 15–34 age bracket that will be the driving force in retail fortunes over coming years. This is by no means a localised trend, and between 2011 and 2015 there was a 60% increase in global food and drink launches carrying a ‘vegetarian’ label. Some companies are already paying attention to this trend and responding. For example, in summer 2016 Pret A Manger actively promoted a flagship store in the UK focused solely on meat-free and plant-based lunch options but branded ‘not just for veggies’ – the innovation paid off, with comparative sales at the branch reportedly up 70%.

"The consumer demand for [non-meat protein] continues to grow, and we are keeping an eye on that because we want to stay relevant with consumers."

Other market-leading companies are developing plant-based alternatives to their prominent brands. One example is Unilever who, having previously dropped a lawsuit against the egg-free Just Mayo from Hampton Creek, subsequently developed its own Carefully Crafted Hellman’s offering.50 Meanwhile, with an ongoing trial of vegan Ben and Jerry’s flavours in the US market, Unilever looks to have an eye on scooping up the nondairy ice-cream market which, in the year to June 2016, had one of the highest dollar growth sales areas and grew nearly 44% in the US.

Such surges in market share are not uncommon as increasing numbers of consumers look for healthier labels and more sustainable products. According to market analysis, Norway’s frozen meat alternatives category grew by nearly 77% in 201452 – the fastest growth within the country’s grocery trade, while in the first half of 2016 the exports of meat-substitute Quorn grew by more than 15%. In the UK, catering to increasingly health-conscious consumers bears financial dividends: high-street retailer Greggs recently posted a 6% rise in sales, which were boosted by its ‘balanced choice’ range.

"Twenty-five percent of US consumers decreased their meat intake from 2014 to 2015, and meat alternative sales grew from $69 million in 2011 to $109 million in 2015"

Clearly, the overall market is not just about catering to vegetarians but to the growing band of health-conscious ‘flexitarians’: 25% of US consumers decreased their meat intake from 2014 to 2015, and meat alternative sales grew from $69 million in 2011 to $109 million in 2015. Those who are still eating animal alongside plant-based products are tending, where they can afford it, to be more discerning about their purchasing habits. For example, analysts highlight the $200bn ‘disruptive’ spending power of the millennial generation in the US who are spending two to three times as much on produce be it grass-fed beef, artisan cheese or locally grown vegetables. As well as scrutinising in-store information for ‘clean labels’, engaged consumers have easier access to data on the relative merits and environmental footprints of different products, and the increase in company’s exposure to online feedback highlights the need for greater attention to quality ingredients and transparency in sourcing.

Some exciting new companies are taking on this challenge. They are creating plant-based alternatives to chicken, ground beef, even eggs, that are produced more sustainably, and taste great.

Potential for product innovation

It makes business sense for established brands to strengthen their less meat and plant-based ranges in order to cater to the increasing demand. For example, Starbucks received nearly 96,000 requests to add almond as a non-dairy option on its menu to supplement the coconut milk and soy milk that was already available. Similarly, around 10,000 customers contacted Pret A Manger to confirm demand when the UK high street retailer floated the idea of an all-plant-based store.

There is a clear appetite for a variety of plant-based alternatives alongside established animal products. While some established alternatives are increasing market share already, such as pea proteins, which grew 361% in new product launches in 2014 and 183% in 201363, others require further research and development. Food tech firms and an increasing number of new-entrant start-ups are looking to innovate and mimic the texture and taste of animal products to appeal to a broad base of consumers, with products such as algae (which may take another decade or so before the price can compete with milk and eggs). Another area that is ripe for development is cultured or lab-grown meat. The technology is exciting investors and environmentalists alike, with an independent study finding that lab-grown beef uses 45% less energy than beef from cows, while also producing 96% fewer GHGs and requiring 99% less land.

Some of these innovative proteins require further research and development, and there is the all too common perception that ‘sustainable’ means more expensive. However, plant-based products can be lower-cost than producing traditional animal-based formulations, and when those savings are passed on to consumers this can further drive growth. Together with consumer education campaigns to highlight the benefits of a more sustainable diet, such price incentives can help to stimulate consumer demand for these options. For example, Sodexo, a leading global food services company, has collaborated with the WWF in the UK to reduce the impact of the meals they serve by creating healthier, more sustainable menu choices, alongside consumer education about the benefits of the partnership.

Practical Strategy Suggestions for Companies

Increasing availability of plant-based and less-meat options, which can be achieved through product reformulation as well as expanding the range of sustainable products;

Adapting choice architecture in retail settings: improved labelling and packaging, alongside preferential positioning/placement of less-meat or plant-based options, offering customer choice;

Competitive pricing, particularly in markets otherwise dominated by cheap, intensively reared and highly processed livestock products;

Promotion of more sustainable choices through marketing and education to increase consumer awareness of the health, taste, cost-saving and wider sustainability benefits of a less-meat diet;

Research and development in plant-based and cultured proteins, and product reformulation.

Next steps

"On a global basis, alternate protein sources will grow faster than meat and seafood, which currently dominate but will begin to wane in coming decades. Global production increases are expected for protein-rich crops including soy, peas, rice, flax, canola and lupin."

Many companies within the food and beverage sector are increasingly alert to the business case for sustainable supply chains – particularly with growing awareness of the systemic threats posed by unmitigated climate change, and the impacts that even small temperature rises will have on food security and future profit margins.

Companies should be encouraged by investors to examine their exposure to protein supply chain risks, and to set targets for diversifying their protein sources. This should include publishing a strategy with key milestones to monitor progress.

This isn’t a fad, it is a shift in consumer behaviour in North America toward plant-based food. That’s a shift we would like to accelerate. Because for the first time, people can pick those foods and not have to compromise on taste.