With the agricultural sector responsible for almost 20% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while also being particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, it is essential to transition the global food system and the financing that underpins it.

The Paris Agreement sought to do that, so 10 years on from its inception, how closely aligned are public and private finance flows to the goals of the landmark agreement, and where does more work need to be done?

What is Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement? |

|---|

Governments have committed to “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”. |

Are public agricultural finance flows aligned with the Paris climate goals?

Governments can use various fiscal tools to support agricultural markets, including subsidies and taxation. This section looks at how closely these tools align with climate and nature goals.

Subsidies are misaligned with climate goals

Reforming harmful agricultural subsidies is one of the most impactful ways that public agricultural flows can be aligned to the Paris climate goals, given the significant negative economic, social and environmental impacts they have.

The OECD defines agricultural support as any form of financial support for agriculture resulting from government policies. It covers measures affecting farm gate prices, monetary transfers to farmers, and public expenditure and investments in services and public goods that benefit the agricultural sector.

In their current form, these measures – especially price incentives and fiscal subsidies – support a global food system underpinned by intensive animal agriculture, exposing companies and investors to significant, financially material risks linked to pollution from excessive fertiliser usage, deforestation and poor health and nutrition outcomes, and prioritising productivity enhancements at the cost of nature and biodiversity.

For example, the World Bank estimated in 2023 that agricultural subsidies are responsible for the loss of 2.2 million hectares of forest per year, equivalent to 14% of global deforestation.

Governments directed US$842bn towards agriculture support between 2022 and 2024, but only 5% of this support was to encourage environmental action beyond existing regulations, according to the OECD.

Of that, approximately 25% was directed to infrastructure and services that promote climate-positive agriculture, with the remainder given to individual producers.

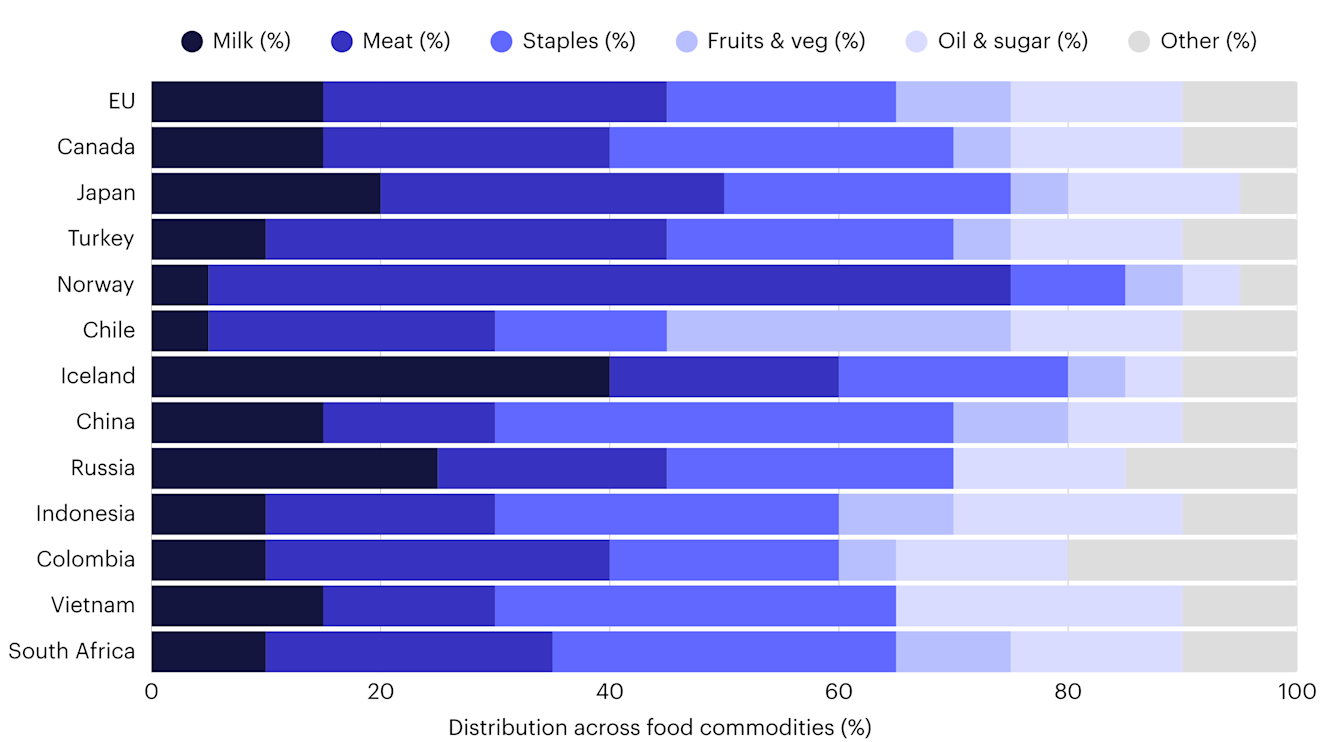

Producer support is largely associated with incentivising the production of high emission-intensive products (e.g. beef, milk and rice) and subsidies that cause harm. This results in greater use of land, fertiliser, water and chemicals, while also reducing the production of and access to nutritious food for the poorest consumers.

Prior to Brexit, for example, UK farms grazing livestock relied on subsidies for more than 90% of their profits, compared to 10% for fruit farms. While more recent data is not yet available, the UK has begun to shift its agricultural subsidies to align with the provision of environmental services (see Table 1).

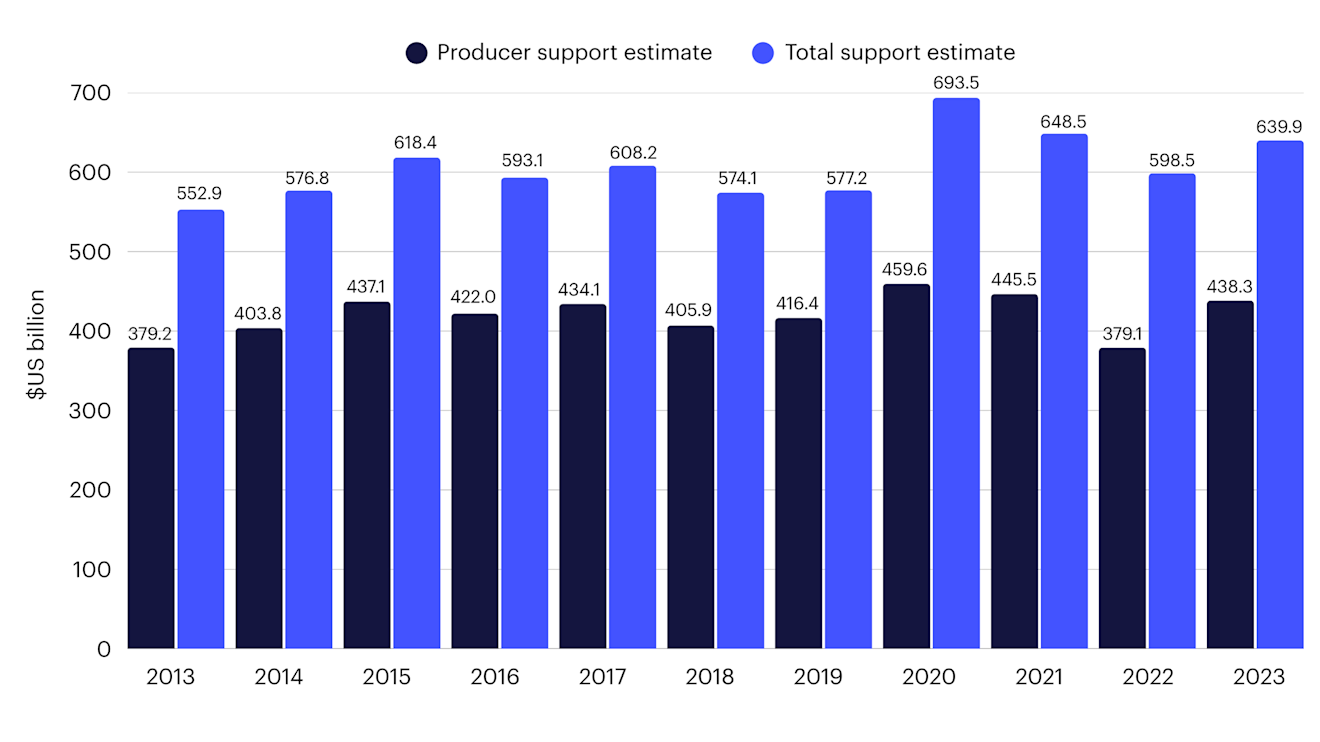

Producer support continues to inform unsustainable agriculture practices, attracting over US$400bn in public finance in the past decade in G20 countries alone, as shown below in Figure 1. Producer-focused subsidies (across all types of agriculture and measured at the farm gate) make up the majority share of these flows.

Figure 1: Aggregate agriculture public support in G20 countries (US$ bn)

Source: OECD (2024). Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation: All data [Data set]. OECD Data Explorer. Retrieved 2 October 2025 from https://data-viewer.oecd.org/?chartId=e32b9bb4-a08f-4453-bd54-95702b1eed7f

Figure 2: Agricultural support across countries by commodity type

Source: Springmann, M., Freund, F. Options for reforming agricultural subsidies from health, climate, and economic perspectives. Nat Commun 13, 82 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27645-2. CC BY 4.0.

International commitments to subsidy reform

Recent UN climate negotiations have generated some momentum on repurposing of subsidies to align with sustainability goals, although tangible action is largely still lacking.

The UK and Brazilian governments launched the Belém Declaration on Fertilisers at COP30, recognising that the production and use of fertilisers for food security, nature, and the climate, needs to be improved. Subsidy reform to address the pollution risks associated with fertiliser mismanagement will be crucial.

At COP28 in 2023, the UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture saw over 100 countries agree that agricultural policies and public support needed to be revisited or reoriented.

The same year, investors, representing over US$7trn and convened by FAIRR, called on G20 finance ministers to repurpose agriculture subsidies to align with climate and nature goals, noting that harmful subsidies incentivise the over-production and over-consumption of certain high-carbon agricultural products, and that the damage caused to nature by subsidy regimes has been estimated at US$4trn to US$6trn per year.

Target 18 of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework explicitly aims to identify subsidies harmful to biodiversity by 2025 and to reduce them by at least US$500bn per year by 2030, but countries have not made progress in meeting the initial deadline.

The World Bank, OECD, and UN FAO are tracking global agricultural incentives; and institutions such as the International Institute for Sustainable Development and the Forum on Trade, Environment and the SDGs have proposed frameworks to identify and repurpose subsidies, but as yet, no single, globally proposed definition or taxonomy for harmful agricultural subsidies exists that can be adopted by countries.

National commitments to subsidy reform

Some examples of countries repurposing subsidies to more closely align with climate and nature goals have emerged, as highlighted in Table 1, but overall progress has fallen short, despite governments committing to various global initiatives supporting climate and nature.

Table 1: National examples of subsidy repurposing in the agricultural sector

Country / Region | Reform action | Climate-positive target |

|---|---|---|

European Union | Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) 2023–27: Ring-fences ~25% of direct payments for schemes promoting activities such as organic, precision and carbon farming It also sets conditionality standards, which link receiving support to meeting rules on environmental, pubic and animal health, animal welfare and land management. | Aims to incentivise carbon farming, biodiversity-friendly practices |

United Kingdom | Environmental Land Management and Sustainable Farming Incentive schemes: Support farmers to adopt environmentally sustainable practices with measurable outcomes, such as habitat restoration and carbon capture, while continuing food production In 2025, DEFRA committed to increasing funding from £800m (US$1.05bn) to £2bn (US$2.63bn) per year by FY2028/29 | Aims to incentivise nature recovery, soil health, carbon sequestration; early results show wildlife restoration and improved practices |

Brazil | Gradual phase-out of credit subsidies linked to deforestation-prone activities (e.g. cattle expansion): Providing low-cost credit under the flagship ABC and ABC+ schemes aimed at promoting low-carbon agriculture. These schemes have been effective in pasture recovery. | Aims to reduce illegal deforestation risk; increase uptake of integrated crop-livestock-forestry systems and generate soil carbon gains |

Denmark | Agreement on a Green Denmark: Will use EU CAP funds to pay farmers to reduce their GHG emissions from nitrogen fertiliser use and to establish a dedicated nature restoration fund | Aims to reduce GHG emissions; incentivise nature recovery |

Sources: European Commission. (2025). CAP at a glance; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. (2025, June 16). Spending review 2025: A commitment to farming; Climate Policy Initiative. (2024). Credit where it’s due: Unearthing the relationship between rural credit subsidies and deforestation; Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark. (n.d.). About the agreements on a green Denmark.

Some policy efforts that support the alignment of public finance with the Paris Agreement are at risk. At the time of writing, the EU’s 2028-2034 spending cycle proposals might lead to a reduction in mandatory environmental requirements for the CAP under the guise of simplification. The plans will be debated by the European Parliament, EU Council and European Commission in 2026.

The benefits of agricultural subsidy reform

Looking ahead, repurposing environmentally harmful input-heavy subsidies could provide a fiscal and financial opportunity while helping to develop climate resilient and sustainable food systems:

Repurposing just a portion of global agricultural support could fully cover the US$260bn per year estimated to achieve global agricultural climate mitigation goals and help countries to meet other national sustainability goals.

By supporting sustainable agricultural practices that reduce emissions and biodiversity loss, subsidy reform can support increased food security and resilience.

Products grown in regenerative agricultural systems or derived from deforestation-free commodities could enjoy broader market access.

Paying farmers directly to deliver ecosystem services and expand into low-carbon agriculture and agroecology can improve income resilience, while reducing fiscal strain.

Taxation and pricing measures

Taxation and pricing measures, which impact agricultural production and consumption, can also be used to counter the negative externalities of climate change in agricultural markets, and there are several significant examples of progress in recent years.

Globally, policymakers are increasingly discussing the true cost and price of food, calling for pricing to reflect environmental and social externalities and to provide a fair price to farmers - the FAO’s State of Food and Agriculture 2023 report offers recommendations to support such efforts, for example.

At a country level, Denmark announced in June 2024 that it would introduce a tax on livestock GHG emissions that exceed the country’s reduction targets from 2030. Revenues from the tax – thought to be a world-first – will be used to help all livestock producers reduce their emissions.

The New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries released a methodology in December 2024 to support standardised agricultural GHG emission estimates on farms, and more broadly, to reduce emissions.

While this development is positive, the roll-back of a proposed emissions tax on the country’s agrifood producers amid sectoral lobbying and political tensions represents a step back. The agriculture sector was due to be included in the country’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) from 2025, but the government announced in 2024 that it would look at “practical tools and technology” that could support emissions reductions instead.

Furthermore, the EU’s ETS also excludes agricultural emissions, making the sector ineligible to receive funds under the Just Transition Mechanism.

Are private agricultural finance flows aligned with the Paris climate goals?

Private finance can play an important role in aligning the global food system with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Agri-food climate finance provided by corporates, commercial financial institutions, institutional investors and philanthropic organisations totalled US$19.2bn in 2021/22, according to the Climate Policy Initiative.

While this marks a nearly sixfold increase since 2019/20, the funding is largely concentrated in upper-middle- and high-income economies, with real and perceived risks, weak enabling environments, limited local engagement and project pipelines among the barriers to scaling up private investment.

Investor financing commitments

Since the Paris Agreement was agreed, investors have made several public commitments to increase climate-aligned investments in the agri-food sector.

For example, in 2021, an almost-US$9trn investor coalition agreed at COP26 in Glasgow to eliminate investment and lending in activities linked to deforestation by 2025, and to increase investment in nature-based deforestation solutions to support the transition to a sustainable agricultural sector.

The Finance Sector Deforestation Action (FSDA) group, formed to implement those commitments, details some of the progress made in its 2025 progress report, although the overarching goal has not been met. All participating investors have:

policies that either cover or address exposure to deforestation;

assessed and disclosed their exposure to deforestation risks;

deepened engagements with companies, banks, policymakers and data providers.

FSDA participants have also increased their investments into nature-based solutions. In 2024, Generation IM raised US$175m in the first close of its Natural Climate Solutions fund, which aims to deliver returns and help transform land use, while the Church Commissioners for England have invested in ~1,400 acres of land to create woodland and restore habitats.

In January 2026, the IIGCC will establish and manage the Deforestation Investor Group, to continue the efforts of the FSDA.

Climate risk disclosures and evaluation frameworks

To support risk management and drive private capital flows towards climate-aligned investment opportunities in the agri-food space, investors need comparable, meaningful company and asset-level data. Several voluntary initiatives and frameworks have emerged in recent years that aim to increase sustainability disclosures among companies and help investors better evaluate their climate and nature risk exposure. These include:

These initiatives and frameworks have gained significant industry traction – the TCFD recommendations were supported publicly by nearly 5,000 organisations since their launch in 2017 and have now been incorporated into the IFRS Foundation’s global standards, while more than 600 organisations representing US$20trn have publicly committed to TNFD-aligned reporting.

Several of these initiatives include sector-specific guidance and tools to support companies and financial institutions. The SBTi has published guidance for the forest, land and agriculture sector related to setting 2050 GHG emissions reduction targets, while the NZIF now defines agriculture, forestry and fisheries as a high-impact sector.

While helping companies and investors evaluate the financial materiality of climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem degradation, these frameworks and initiatives remain voluntary, therefore limiting the extent to which they can shape private finance flows.

Furthermore, as political sentiment shifted in the US in 2024, several prominent investors and companies withdrew from voluntary net-zero initiatives. There are indications, however, that many asset managers and owners continue to align their investments with climate commitments, albeit more quietly, with several analysts suggesting that the solid economics of decarbonisation have already set the transition in motion.

Latest analysis of Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index shows limited climate progress

FAIRR assesses 60 of the world’s largest, listed protein producers on the net-zero and Scope 1,2, and 3 targets they set, the ambition of these targets, and whether they are validated by the SBTi.

Companies have made significant progress in setting emissions targets, with the number doing so doubling between 2021, when FAIRR last published a report on agricultural finance, and 2024, when the most recent iteration of the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index was published. But the proportion of companies disclosing their emissions, or setting science-based, Paris-aligned targets, is still low (see Table 2).

Table 2: Company progress on setting targets and disclosing emissions

2021 | 2024 | |

Companies that have set scope 1, 2 and 3 targets | 25% | 52% |

Companies that set science-based scope 1, 2 and 3 targets | 7% | 18% |

Companies that share their scope 1,2, and 3 emissions | 12% | 22% |

Source: Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index 2024

Furthermore, movement in absolute emissions reductions has also been limited. In 2024, almost two fifths of index companies disclosed an annual reduction in emissions against a comparable base year since 2020, but only two reduced their emissions by more than 3.03% year-on-year, in alignment with the SBTi FLAG guidance.

While company ambitions to address climate risks have clearly improved, their ability to measure and report on actual emissions reductions remains limited, as is their transition readiness, demonstrating the importance of legislation to make disclosures mandatory and drive measurable action.

Read more about how protein producer commitments and practices have developed in FAIRR’s report, Taking Stock of Industrial Animal Agriculture.

Regulatory frameworks impacting agricultural finance

Financial policies and regulations can help shape investment incentives, transparency and accountability in the agri-food sector. As a sector that is both a major emitter and highly vulnerable to climate impacts, such regulations are increasingly important to address the Paris climate goals.

The EU Deforestation Regulation and the corporate sustainability due diligence and reporting directives in the EU are examples of laws and directives that have been passed since the Paris Agreement came into force. Although world-leading when originally drafted, the final shape of these measures is now uncertain.

For example, the EU’s Omnibus Package bundles together some of the bloc’s sustainability reporting and due diligence laws to boost Europe’s competitiveness and reduce compliance requirements on companies.

The simplification of such regulations, as currently detailed, will reduce the number of companies in scope for reporting, postpone or remove reporting deadlines and sector-specific standards, and dilute the obligation for agri-food companies to adopt climate transition plans to meet Paris Agreement targets.

These efforts could make it more difficult for investors and regulators to obtain reliable, comparable sustainability data, making risk management and investment decision making related to financially material sustainability risks more difficult. In turn, this could negatively impact finance flows towards sustainable agriculture. The Omnibus negotiations are ongoing, and their impact will ultimately depend on the outcome of policy negotiations.

Political headwinds have also impacted the US regulatory environment in recent years. While California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act and the Climate-Related Financial Risk Act are moving forward toward implementation, US federal climate disclosure rules, finalised in 2024, were subsequently dropped in the face of political opposition.

Financing mechanisms: Thematic bonds and voluntary carbon markets

Financing mechanisms that can be used to channel private investment flows towards climate-aligned goals do exist, but these are often limited in scope or lacking a supportive governance framework.

For example, green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked (GSS+) bonds allow public and private projects, governments or corporates to raise capital, with coupon rates tied to meeting environmental or social performance indicators, while providing investors with returns, thematic alignment and diversification.

The International Capital Markets Association has set standards on annual reporting, KPIs and independent verification for such bonds, while the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) launched the Agrifood Transition Framework in 2025 to provide guidance on financing a just, and science-aligned, transition in the agri-food system.

Cumulative issuance of GSS+ bonds totalled US$6.9trn as of 31 December 2024, according to the CBI. Just over US$1trn in deals aligned to the CBI’s methodology were priced in 2024, representing an 11% increase on the US$947bn issued in 2023, and a near fivefold increase on the US$200bn issued in 2017.

Several countries have developed, or plan to develop, sustainable or green taxonomies that can support private capital flows into thematic bonds focused on agriculture, including Australia, New Zealand and Thailand.

Most recently, Brazil announced the Brazilian Sustainable Taxonomy at COP30 and proposed plans to establish a “Super Taxonomy”, which would allow investors, governments, and companies to compare products and activities across countries.

Voluntary carbon markets also provide a channel for aligning private investment with the Paris climate goals, and agricultural carbon credits represent a small but growing segment of this market.

Some 20 million agricultural-related carbon credits were issued in 2022, representing just over 1% of the 1.7 billion credits issued overall that year, while BloombergNEF estimates that carbon farming could produce credits worth US$13.7bn annually by 2050.

Yet questions remain around the effectiveness and credibility of carbon credits, with questions around the quality, permanence, and transparency of some offset projects, while leakage and high verification costs can also pose challenges, as explored in FAIRR’s Insight on the topic.

The launch of a framework to support the issuance of high-integrity carbon credits by the governments of France, Kenya, Singapore, the UK, and Panama at COP30 is positive, with the framework aiming to inform national policies and incentives that can drive more private sector investment into climate solutions through carbon markets.

Despite their challenges, these financial mechanisms represent an opportunity for private finance to align with global climate goals, and developments from COP30 indicate an appetite among policymakers to support that alignment.

More action needed to align financial flows with the Paris Agreement

In the 10 years since the release of the Paris Agreement, progress in aligning public and private finance flows in the agricultural sector has clearly been limited.

Although countries have committed to shifting public subsidies to meet climate goals and to reform harmful agricultural subsidies, with some examples of support for sustainable and regenerative agriculture, there is still no international consensus on defining and tracking harmful subsidies. Furthermore, national efforts to incentivise emissions reductions through measures such as trading schemes have also stalled due to political opposition.

While there has been some progress in the financing commitments made by investors, the development of voluntary frameworks to disclose and manage climate risk, and the growth of instruments such as thematic bonds and carbon credits, the proposed roll-back of environmental regulations in the EU under the guise of simplification is concerning.

Overall, more action is needed. Transitioning the global food system, and economy, to align with the Paris Agreement goals is only possible with the support of public and private finance, and this requires collaboration at all levels – from international bodies, national and regional policymakers, investors and civil society.

FAIRR has several resources to help investors understand the material financial risks associated with intensive animal agriculture in relation to climate and nature issues, and it will continue to represent investors in its work with policymakers.

Read more about FAIRR’s climate work

Read more about FAIRR’s biodiversity work

Read more about FAIRR’s policy work

Written by

Policy Director

Policy Officer