The landmark 2006 Amazon Soy Moratorium, under which grain traders voluntarily committed to not buy soy from areas deforested after 2008, is under threat, posing significant risks for investors and the future of sustainable soy production.

At the same time, Brazil and China have been forging increasingly close ties when it comes to soy, driven by increasing demand from China and trade frictions with the US.

In March 2025, Brazil exported approximately 15.7 million tons of soybeans, three-quarters of which went to China, marking the highest monthly amount ever exported to the country, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF).

This could represent an opportunity for the two nations to show coordinated leadership on reducing deforestation. Conversely, without adequately protecting the Amazon and other at-risk areas, increased trade between Brazil and China could exacerbate the environmental destruction of these ecosystems.

The sustained attacks on the Soy Moratorium risk undermining any such leadership and make the latter scenario more likely.

Its potential dismantling also exposes companies and shareholders to financially material risks and significantly impacts Brazil’s credibility as the host of COP30, as this Insight piece explores.

What are the latest developments on the Amazon Soy Moratorium?

At the end of April, it was reported that Brazil's Supreme Court will allow the country's biggest farming state to withdraw tax incentives from signatories to the Soy Moratorium.

Mato Grosso state, which supplies almost a third of Brazil's soybeans, had passed a law in November 2024 reducing the tax benefits for companies adhering to the agreement. The Supreme Court’s recent decision upholds that law, whose enforcement had been suspended.

Although Justice Flavio Dino acknowledged that the moratorium was an important conservation tool, he noted that it cannot be used to constrain state actions. Worryingly, a similar bill has also been filed at the National Congress, threatening the moratorium on a national level.

Some of the world’s largest aquafeed companies, including Mowi, BioMar and Skretting, described Mato Grosso’s law in a public statement as “an existential threat” to the future of sustainable agricultural resources globally. A group of 70 civil society organisations has also called for the Soy Moratorium to be defended.

Separately, the Mato Grosso farmers’ lobby, Aprosoja-MT, filed a lawsuit in May against global grain companies, including ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus Company, according to documents seen by Reuters. This lobby group are trying to win compensation for losses the Soy Moratorium has allegedly imposed on Brazilian soybean farmers.

This is not the first time Aprosoja-MT has lobbied against the moratorium – in December 2024, it asked Brazilian watchdog CADE to end the moratorium, saying it fostered "a purchasing cartel" and harmed farmers who comply with the forestry code.

That month, another lobby, the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries, balloted its members on a proposed change in the way the moratorium is monitored, the Guardian reported.

That change would see individual fields, rather than entire farms, being assessed, which critics say would allow growers to cherry-pick which areas of their land comply. Conservation groups threatened to withdraw from the moratorium if the change is implemented.

Why do these developments matter to investors?

Deforestation exposes companies and their shareholders and lenders to a host of material risks, as highlighted in FAIRR’s research briefing and recent Insight article.

These include reduced productivity and insecure supply chains stemming from land degradation and soil erosion, to associated increases in operating costs and reductions in profits, increased lending costs and default risks.

While the Soy Moratorium has not halted deforestation in the Amazon entirely, it has been hailed as a success, allowing soy production in Brazil to expand while seeing deforestation and conversion decline, at least for a period of time. Between 2004 and 2012, deforestation dropped by 84%.

The recent attempts to pare back and derail the Soy Moratorium are significant – potentially creating loopholes that would allow more deforestation-linked soy to enter supply chains and undoing the economic and environmental achievements of the last 19 years.

Investors have increasingly recognised the risks to long-term sustainable returns posed by deforestation, and signalled their support for the moratorium in 2019, when FAIRR coordinated an open letter to the Brazilian government calling for the protection of the agreement.

It was backed by investors representing US$3 trillion in assets, including Legal & General Investment Management, Robeco and BMO Global Asset Management as well as corporate signatories such as Tesco and Marks & Spencer, showing the significant support for deforestation-free soy production.

The statement highlighted that protecting the rainforest is vital for long-term agricultural output globally, due to the role it plays in regulating rainfall and temperatures.

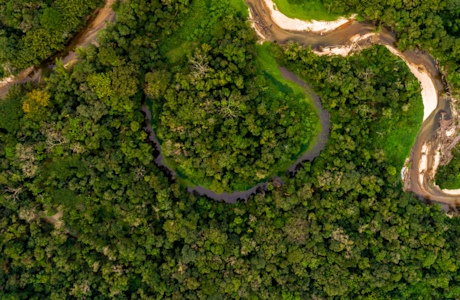

Climate change and deforestation have already pushed the Amazon to the brink of destruction. A slight further temperature change or continued deforestation could trigger an irreversible tipping point, which would turn much of the rainforest into savannah.

This would be catastrophic for farmers, protein producers and the world at large. Natural ecosystems underpin economic activity, with 55% of the world’s gross domestic product (approximately US$58 trillion) dependent on nature’s resources.

The path to COP30 – how can policymakers take action?

To benefit from long-term economic investment, Brazil needs to ensure deforestation is addressed, particularly as markets such as the EU look to impose stricter controls on imported goods to ensure they do not come from deforestation-linked areas.

Furthermore, Brazil and China need to ensure that their increased soy trade does not exacerbate deforestation or work against the climate and nature goals that both countries have committed to, through the Brazil-China joint statement on climate change, for example.

If efforts to weaken or halt the soy moratorium succeed, it would make it harder for global companies to meet their science-based targets, while also harming Brazil’s reputation as a sustainable producer of agricultural commodities and its international credibility, especially as the host of COP30 later this year.

Policymakers in Brazil and China need to support voluntary efforts to address deforestation risks while also working toward mandatory regulation to enable deforestation-risk supply chains. This would be a true legacy of the COP30 summit.

FAIRR insights are written by FAIRR team members and occasionally co-authored with guest contributors. The authors write in their individual capacity and do not necessarily represent the FAIRR view.

Written by

Helena Wright PhD

Policy Director

Dr Helena Wright joined FAIRR in 2021 as the Policy Director. She leads on engagement with governments, investors, regulators and industry bodies, to co-develop policy solutions to tackle the challenges and opportunities associated with intensive animal agriculture.