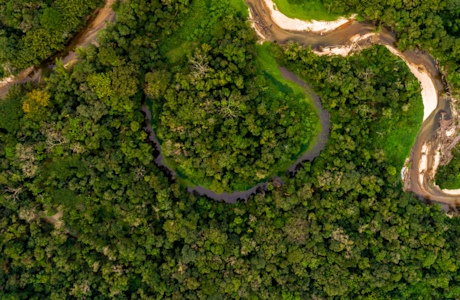

Intensive animal agriculture contributes to deforestation when forest is cleared either for livestock grazing or for arable crops, many of which are grown for animal feed. This article explores the impacts and risks of deforestation, with a focus on beef and soy (a component of feed), and examines the regulations and material risks for investors.

Why deforestation poses risks to animal agriculture?

The production of animal proteins requires the transformation of natural landscapes, including through deforestation. This transformation has contributed to exceeding the land system change planetary boundary, one of nine identified by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Deforestation also pushes the world closer to, or further beyond, other planetary boundaries. These include the critical thresholds of climate change, as forest carbon stores are released, leaving behind fewer trees to sequester CO2; and maintaining the integrity of the Earth’s ecosystems.

Intensive livestock farming is recognised as one of the main drivers of changes in ecosystem diversity, as well as habitat and biodiversity loss – phenomena that undermine nature’s ability to provide the fundamental ecosystem services on which societies, economies and all species rely.

Around 50% of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, with livestock and animal feed production responsible for 77% of that figure. Beef and soy are the largest drivers of tropical deforestation, with over 75% of all soy destined to become livestock feed.

Environmental impacts of deforestation

If planetary boundaries continue to be exceeded, natural cycles and vital environmental processes will be severely disrupted, hindering the planet’s ability to stabilise itself in the face of change.

Animal protein producers are dependent on ecosystem services and a stable climate, making them extremely vulnerable to physical environmental risks. Excessive deforestation exacerbates the effects of climate change by reducing rainfall levels in local areas. This increases temperatures, diminishing agricultural productivity and yields.

High-risk region case study

Brazil, a major global supplier of animal feed and beef, suffered its worst drought in decades in 2020 and 2021. Research found this was likely due to reduced rainfall caused by local deforestation, alongside rising temperatures. The world’s second-largest corn exporter saw yields drop and imports increase, while soy and corn prices spiked.

The beef sector will be increasingly impacted by weather-related pressures if its dependence on confinement and semi-confinement operations continues. Nature Communications predicts that forest loss will reduce dry-season rainfall across the Amazon basin by 21% by 2050, with productivity-associated revenue losses of US$180.8 billion for beef production. The conversion of the Cerrado savannah into open grasslands or planted crops has already reduced yearly rainfall by approximately 8% over the past three decades.

Furthermore, a 2023 study predicts that deforestation will reduce local rainfall across the world's rainforest biomes, potentially causing crop yields to decline by 1.25% for every 10-percentage point change in forest cover.

Soy farming's environmental impact

Most of the world’s soy comes from the Americas, with the US and Brazil accounting for almost 70% of production, followed by Argentina (11.7%). Exports from Brazil and Argentina – both high-risk deforestation areas – are largely destined for farmers in Europe and China, where soy is a key ingredient in animal feed. Global forests are, therefore, increasingly at risk, if meat consumption continues to grow.

Although North American protein producers tend to source most soy locally, the sheer volumes they use mean that they contribute to deforestation, because they source the remainder from locations with high deforestation levels. Furthermore, locally sourced soy will increasingly have to be supplemented by soy from other regions because of climate change.

Most of the world’s soy is used to feed chickens (53%), followed by pigs (29%) and farmed fish (8%), with much less used to feed cattle (<3%). Alternative feed sources that could reduce environmental impacts have not been adopted at scale, and soy remains one of the cheapest protein sources available to farmers, while alternative legumes are currently less competitive and less widely available.

Cattle farming's environmental impact

Cattle raised for either beef or dairy are pasture-raised or grain-fed – around 90% of beef cattle in Latin America and around 50% - 60% in Australia are primarily pasture-raised. This requires significant swathes of land to be cleared for grazing, increasing deforestation rates in South America and Eastern Australia, which is now designated a deforestation hotspot by WWF. In contrast, many larger-scale commercialised beef operations combine grass- and grain-fed systems. Grain-fed cattle make up more than 60% of total beef production in the US, driving soy deforestation through feed import demands.

A common feature of modern beef production is its vertical segmentation, contrasting with integrated systems for pork and poultry. Cattle typically change hands several times before they reach abattoirs, meaning supply chain visibility tends to be poor. Farmers usually breed and raise cattle and sell them to direct suppliers, who fatten them up until they reach slaughter weight. The extent of this segmentation differs between countries.

The Brazilian meatpacker Marfrig, assessed as part of the 60 protein producers in the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index, has around 30,000 direct and 60,000 - 90,000 indirect suppliers across the Amazon and Cerrado biomes, highlighting the complexity of beef supply chains. Brazilian meatpacking companies have been linked to deforestation through the purchase of cattle kept on farms that have cleared land illegally. The cattle are often moved to ranches designated as deforestation-free before being sold.

Tracing and monitoring indirect suppliers is essential to guarantee deforestation-free products linked to cattle. Progress has so far centred mainly on direct suppliers, which are more easily tracked and often account for the minority of the herd.

Deforestation regulations and developments

At COP26, more than 100 countries, representing over 90% of the world’s forests, pledged to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. This was followed by the launch of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership at COP27, which aimed to enhance cooperation between countries towards delivering the target.

Since 2022, several initiatives and regulations have been released that focus on deforestation:

The Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi): Released specific guidance for companies in the forest, land and agriculture (FLAG) sector on how to set emissions reduction goals, including zero-deforestation commitments.

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD): Launched its first version of recommendations for organisations to act upon nature-related dependencies and opportunities.

The Science Based Targets Network (SBTN): Released guidance for companies that wish to set science-based targets for nature across biodiversity, land, freshwater and oceans.

EU Deforestation-Free Regulation: Entering into force in December 2025, this regulation aims to address deforestation stemming from the sourcing of commodities such as soy and cattle. Stakeholders that import or sell such commodities to the EU will need to prove that they did not originate from deforested land or contribute to forest degradation.

According to the Accountability Framework Initiative and the SBTi, companies should make and implement zero-deforestation commitments by 31 December 2025 to source all, or nearly all, their products from land that has not been deforested after a given cut-off date. A target date beyond 2025 is considered insufficient and allows too many years of deforestation.

The cut-off date, recommended to be no later than 2020, refers to the date after which land that is deforested cannot be considered deforestation-free, making it essential to any commitment. Clearance after that date would render the area non-compliant with non-conversion commitments. Not having a cut-off date could incentivise a company to accelerate deforestation rates and land clearing until its zero-deforestation target date. Certification body ProTerra uses an August 2020 cut-off date, while soy certifier RTRS has set 2009 and 2016 for its zero deforestation and zero-conversion cut-off dates, respectively.

Why deforestation is a material financial risk for investors

Addressing deforestation is becoming a mainstream commercial imperative as the world responds to climate change and biodiversity loss. This poses a growing material risk for producers and investors that fail to respond.

Many companies assessed in the Coller FAIRR Protein Producer Index that source or produce beef and soy do not address deforestation risks in their supply chains, while a few have addressed the new SBTi FLAG criteria alongside other regulations around deforestation.

While some companies are responding to these regulations, many do not have the necessary commitments in place, or the tools needed to monitor implementation. Most Index companies do not have full traceability of their soy and cattle supply. A lack of monitoring means companies cannot track overall progress and supplier compliance with their commitments.

Summary

Deforestation caused by intensive animal agriculture has serious and widespread environmental impacts that deplete the ecosystem services on which people and agriculture depend. Despite worldwide pledges and guidance on halting deforestation, many companies have yet to address deforestation risks in their activities and supply chains.

Reference

[3] Chatham House. (2020). Resource Trade.Earth.

[5] HM Treasury. (2021). Final report – The economics of biodiversity: The Dasgupta review.

[6] Mongabay. (2021). Amazon and Cerrado deforestation, warming spark record drought in urban Brazil.

[7] Our World in Data. (2019). *Land use*. https://ourworldindata.org/land-use#total-agricultural-land-use

[10] Statista. (2023). Soybean production worldwide 2012/13–2022/23, by country.

[11] Stockholm Resilience Centre. (n.d.). The nine planetary boundaries.

[12] Universidade de Brasília. (2018). Chuvas no Cerrado diminuíram 8,4% em três décadas.